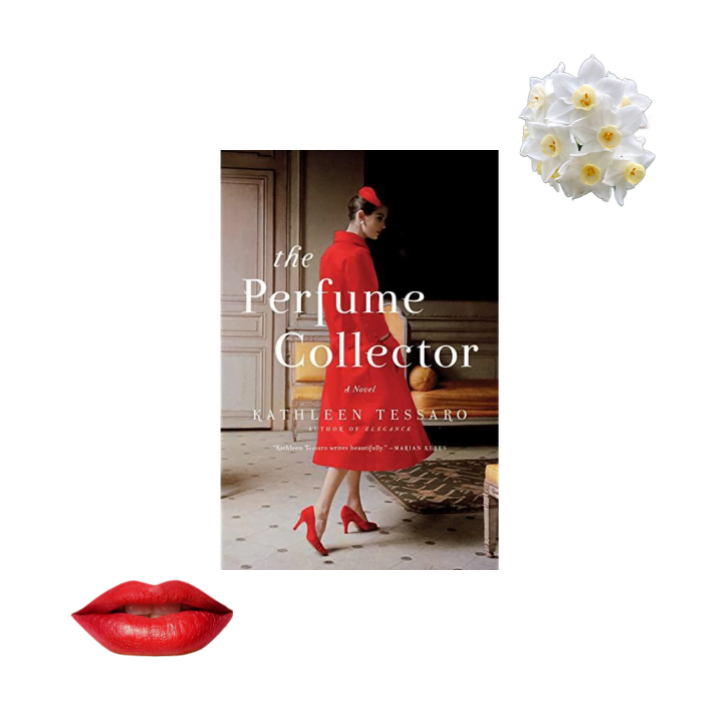

The Perfume Collector by Kathleen Tessaro Book Review

Can anyone write a perfume-related book that is remotely happy for once?

Alright, this one is happy in places. The Perfume Collector by Kathleen Tessaro has its moments of horrible misery, but there are moments of delight as well.

This historical novel alternates between the stories of Eva d’Orsey growing up in the 1920s and of Grace Monroe, a newlywed socialite in the 1950s.

Grace Monroe learns someone by the name of Eva d’Orsey has left her a colossal inheritance. Grace has no idea who Eva is. Shenanigans ensue. Perfume is tangentially involved.

This was far less painful than the steady drip of prosaic heartbreak that was Erica Bauermeister’s The Scent Keeper. The pain and sadness of The Perfume Collector is of the grisly kind common in novels set in the first half of the twentieth century. Streaks of gruesome war recollections, poverty, drug addiction, disturbing treatment and abuse of children, and various bigotry -isms (especially sexism — pointed a-woman’s-place-is-xyz remarks abound on every other page) run through the novel.

It’s ghastly in places, but the ghastliness is built into the historical world building such that one generally adjusts and expects it. You can hardly expect to read a book set in 1920s-to-1950s Europe and not be subjected to something nasty.

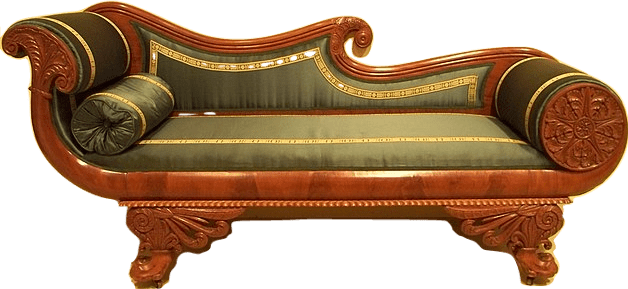

The other thing that modulates the horrors of The Perfume Collector is a counterbalance of characters and moments that make you smile, especially in the story of Grace Monroe. The endearing devotion of the amusing best friend, the easy flirtation with a love interest, the delightful detective-novel-esque romp of following clues throughout the novel all keep a slice of lightness in every other chapter at the very least.

While the story of Eva D’Orsey is heavier, far more distressing and complex, Grace Monroe’s timeline adds much-needed levity. The mixture makes for a book that continually propels you to keep reading, either to find out more about Eva or to enjoy the escapades of Grace.

This unexpected historical mishmash of a heartbreaking tragedy and an upbeat romp shouldn’t work, but it does.

For a book called The Perfume Collector, the perfume in question does show up rather late in the novel, but once it’s there, it’s a consistent peripheral through line. It is never central to the characters themselves — we don’t really get to see inside the mind of anyone obsessed with perfume — but it winds up being a central element tying all the stories together.

The world-building here is thorough and immersive. In moments of revelry and delight, it’s magical; in moments of horror, it’s spine-chilling. The language, the fashion, and even all the rather lazy transparent sexist comments that look at you as if to say “See how constrained women were back then?” — all of it contributes to the cohesive atmospheres of each respective time period and place.

The order in which the story is teased out is also masterful. The alternating Eva and Grace chapters are an enormously effective device to keep you reading as you race to unravel the mystery from two alternating ends. The placing of hints and inter-connected clues is just right. I didn’t anticipate the twists in the story except when dramatic irony made it intentionally obvious (such as meeting a mystery character in Grace’s story and immediately recognizing her from Eva’s). Tessaro has a thorough understanding of pacing, telling a compelling story out of order, and how to maintain hurtling momentum in a mystery novel.

The construction of the story itself is also rather beautiful. Looking back on the whole thing after finishing the book is like looking down at a thousand-piece jigsaw puzzle you just completed, wondering at the fact that when you first began you had no idea what the picture would be. Everything just comes together. The pieces snap together perfectly, and the feeling of looking back is bittersweet.

The Perfume Collector successfully pulls off that sense of Pyrrhic victory integral to making so many novels full of misery not feel miserable in the end: horrible things happened, but at least our main character has a delicious new life they wouldn’t have had if they hadn’t pursued this venture to its end. The connection between the lives of Eva and Grace spreads some of this gladness over the entire story, even the most heartbreaking parts. This makes for a satisfying read. It leaves you feeling a perfect poignant mixture of joy and sorrow in something like a 3:1 ratio, which is a perfect rewarding ratio for ending a book that is tragic in many places without making the reader angry or miserable.

There’s not much to note in the handling of scent in The Perfume Collector. Fragrance is the through line pulling all the stories together in the same way that any other chosen commodity might be. While The Scent Keeper played with new ideas around scent and its use in vivid description — to gorgeous effect — The Perfume Collector remains rather distant. The discussion of scent only goes so deep as observing that it is often closely tied to memories.

In fact, The Perfume Collector seems to take a rather irritating shine to this idea of perfume being all about sex. Sure, this was a predominant idea in fragrance marketing for ages, but as a recent New York Times piece noted, it’s not the only one out there. These days, fragrance is generally marketed as a doorway to experiences, places, and moods, an entirely personal choice for oneself.

It would have been interesting to see more of this sort of philosophy represented in the discussion of scent in The Perfume Collector. Instead, most of the discussion of the merits and purpose of perfume rests on its raw sex appeal. It’s vaguely insulting and simply uninteresting for so much of a perfume novel to posit fragrance as this carnal femme fatale thing, all about pheromones and seduction and sin.

The Achilles’ heel of The Perfume Collector is ultimately the problem of character motivation. Throughout the stories of both Eva and Grace, it is scarcely clear why any character is doing what they’re doing. The plot is pushed and pulled along by a vortex of horrors and the momentum of detective-like discovery, but the characters seem to have almost nothing to do with it. It does take you out of the fun (and the misery) a little to be utterly befuddled as to why a character is acting the way that they are, what caused this change in their personality or their mind, what made them think to do what they did.

The most egregious example is the personal development of Eva D’Orsey. Over the course of just a few pages — and no more than a few weeks in the story — she goes from being an incredibly awkward, obedient, shy girl, easily flustered and naive, to a cool exemplar of the femme fatale, gorgeous, seductive, powerful. This is all explained away with perhaps two sentences about the magic and mystery of becoming a woman as well as allusion to a single highly traumatic event. From this point on, Eva is the most desired woman in every room, an incredibly skilled socialite, and a master manipulator, controlled only by her own stereotypically-drawn tragic relationships with sex, drugs, and toxic people and places she won’t leave behind.

I, for one, don’t buy it.

We’re supposed to believe that, just by merit of turning — what, twelve? thirteen? — a switch flipped, producing an entirely new Eva? That some magical component of becoming a woman turned this pipsqueak goody-two-shoes into this person with incredible social savvy and charm? Perhaps much of that development happened off the page, in days and weeks and months we don’t get to read much about, but the difference and lack of logical explanation for the change is jarring.

A similar example is that of Grace, who is similarly drawn as rather awkward and failing her navigation of the London socialite scene at the beginning of the novel. She’s exhausted and out of her depth, and heartbroken about the way things are with her husband to boot.

And yet, all of a sudden, she lands in Paris and perfectly naturally strikes up a delightful flirty relationship with her lawyer? Teases him and is teased in turn? Shamelessly speaks horrible French? Goes around laughing and buying stunning black Balenciaga dresses? I know a change of place can do a lot for a person, but the seemingly entirely unexplained changes in Grace’s personality are still odd to watch.

Perhaps much of it is because Grace is getting away from the things that confine her — London, the socialites, her incredibly annoying husband — but even so, her changing into a person she’s seemingly never been before just because she’s in Paris, while still internally struggling with the idea of making any sort of decisions for herself, seems quite unlikely.

In addition to Grace’s coolness and flirtation with the lawyer, her frantic we-have-to-find-out-the-answers demeanor also seems overexaggerated and unwarranted. From the instant they meet, Grace is asking “why” far too many times and with far too much energy for we’ve come to expect of this timid and awkward woman. There’s no obvious motivation for the amount of galloping energy and drive she pours into finding answers about Eva. Sure, there’s curiosity, but the amount of frenetic determination and drive is strange.

Even a cliché brooding monologue about feeling empty inside and wondering whether Eva held the key to understanding herself (or something of the sort) would have been preferable to the utter lack of explanation provided for this sudden burst of energy. Sure, if someone I didn’t know left me a huge inheritance I’d want to find out more too, but the amount of frantic determined clue-hunting Grace does in Paris needs more context to make sense.

Even the minor characters are riddled with befuddling flips and inconsistencies. One almost comical example is the way André transforms from a bitter (and very gay) man who cannot stand the sight of Eva to a fanatic madly in love with her, simply by smelling her sweat. This girl must have some downright magical sweat for its scent to have that effect on a person.

And then there’s Yvonne. Upon discovering her husband has a mistress, why does she introduce herself to said mistress and gift her an enormously valuable piece of real estate in the heart of Paris and an extraordinary portfolio of stocks? And why does she want to buy that apartment back so badly she’s willing to pay double its market value? No background is given to explain these choices.

It seems that things happen because the plot needs them to happen. It drags the characters along like marionettes, contorting their personalities and choices this way and that without any plausible explanations as to why anyone does anything.

All these oversights make the novel feel shallow and two-dimensional at times. It’s hard to stay immersed in the plot when the characters seem to be nothing more than cardboard cut-outs without a reasonable leg to stand on.

In addition to this character-building weakness, the cavalier way The Perfume Collector treats some truly alarming subject matter leaves something to be desired.

The most disturbing thing in The Perfume Collector is by far the way Eva is trapped her whole life being manipulated, mistreated, and used from an incredibly young age. It is only in the last few chapters of the novel that we get a benchmark for how old Eva was during most of the events described. Estimating timeframes and counting backwards brings the reader to the disturbing realization that Eva’s transformation into a sex-goddess-femme-fatale was at… what, age twelve, thirteen? The whole book describes her in these years as so cool, so charming, so socially savvy and adept, so respected, admired, and lusted after in various elite socialite circuits…

And she was thirteen the whole time?

Listen, I know times were different, but were they really that different? When I look at a twelve, thirteen, fourteen year old girl, I see a child. In what world does a kid that young pass as the most in-vogue elite socialite? As the most desirable woman in all of New York? Who let this child into all these casinos? How were all these men — many painted in a mostly or entirely positive light — sexually involved with her from the age of twelve or thirteen like it was nothing?

It’s incredibly disturbing, and the way it’s revealed near the end leaves the reader feeling disgusted and rather cheated. Sure, the manipulation of Eva, the tight corners she’s been trapped in, the men and conventions and habits trapping her, all these things have been awful the whole time — but the sudden revelation of how young she was paints it all in an entirely new light.

Only once does anyone in The Perfume Collector express shock and disgust at a man whisking her away as a young child, and the response is a dismissive muddle along the lines of “Who can say who seduced whom?” The original speaker sees some merit and relatability in this answer, and the matter is dropped.

Who can say who seduced whom? Well, I don’t know about you, but between the wealthy, titled, experienced middle-aged-man and the destitute twelve-year-old, my money’s on the former.

Of course authors can portray and discuss horrible things without implying any agreement with them, but the issue of Eva’s extreme youth could have been handled to better effect. The book makes a point of displaying casual very sexist remarks by men in every chapter. It’s heavy-handed, but an effective world-building device that makes it clear how terrible things are and leaves us someone to side with against them — the female protagonists. The way Eva’s age is hidden away through most of the novel and dismissed, however, is a missed opportunity.

Of course the whole thing plays into the feeling of deep and utter tragedy, but it also feels like the reader is cheated out of realizing it through most of the novel. Twelve- and thirteen-year-old Eva is written as this extremely sexually experienced, desirable, cunning adult femme fatale, drinking and smoking and seducing people left and right, and the reader isn’t even given much of an opportunity to realize how young she’s been the whole time.

Perhaps this is meant to put the reader in the perspective of all these people taking advantage of Eva — but frankly, that’s a disgusting perspective I didn’t ask to be put in without adequate context that makes it clear that’s what going on and that it isn’t the right way to see her. Also, that idea seems to imply all the men controlling her weren’t preying on her age — or didn’t even realize it — which is entirely impossible.

All this who-seduced-whom and incredibly mature description of teenage Eva is quite distressing without a debrief where somebody, anybody, in this book acknowledges how wrong and disturbing it all is. It seems the reader is expected to side with this moral ambiguity created by the sheer power of female sensuality — that no matter how old you are in years, one day you just wake up with breasts and suddenly you’re a fully-fledged sophisticated adult capable of seducing middle-aged men left and right.

Even if no one in the book ever properly recoiled in sadness and disgust at the fact, at least letting the reader clearly know how young Eva was the whole time would convey the shock value effectively rather than dismissing it and leaving the reader feeling tricked by the mature description. Instead, Eva’s incredible youth is treated as an unexplored footnote, as if her age in years doesn’t matter since she’s so good at playing this sensual socialite. I don’t like that conclusion at all.

All this is not to say that I needed somebody to come out and say “Listen up, everyone. Child abuse is bad.” But I needed some acknowledgment of the fact, either in the form of other characters’ reactions or in description that persistently frames this as a disturbing thing the whole way through rather than burying the fact for most of the novel.

As it were, this facet of The Perfume Collector felt really appalling — not just in the subject matter, but in the blasé way it’s excused by description that focuses entirely on Eva’s inexplicable maturity.

Overall, each character is well-written, consistent save for all the aforementioned jumps where their personality and choices sharpy shift without any explanation. Each of them is a delight to read, particularly in the more joyful and comfortable story of Grace. Her chemistry with the lawyer, although inexplicably instant, is delicious and fun, and her relationship with her best friend provides comfort and several good laughs.

Grace’s story generally feels like a rather over-simplified caricature of clichés towards the end, but it’s a feel-good caricature. Here is the comforting, endlessly supportive best friend. Here is the contrite but instantly extremely annoying husband. Here is a rapid descent towards making out with your lawyer in a hallway. It all feels a little too simple, hurtling towards colossal life choices with far too much romantic optimism.

But after the misery of much of the rest of the novel, that cheesy oversimplified trot towards a happy ending feels really good. Everything else about The Perfume Collector makes you thirsty for the pleasure of good things happening easily. When things all fall into place too simply and too easily in the end, the simple pink pleasure of it is so luscious I can hardly complain about its lack of realism.

The ending pulls The Perfume Collector up from some three-and-a-half out of five stars to a solid four in my eyes. The clever coils of the story and the payoff of good things finally happening make every miserable prior chapter feel all the more worth reading.

When I set out to read a historical fiction novel, I’m always slightly worried by the prospect of being overwhelmed by things to keep track of, or else simply bored to death. The Perfume Collector deftly avoids both. Its pacing and storytelling continuously push you forward in a way that is utterly modern, while the world-building is so airtight that you’re entirely enchanted by the quirks and horrors of another time.

The storytelling is clever and minimal where it needs to be. There are parts I’m still wondering about after reading, thinking, “But was that… ohhhhhh.” While the main mysteries are all puzzled out by the end, there are smaller ones you’re left to work out for yourself. There’s an excellent mix of levels of reader-as-detective in The Perfume Collector, ranging from painfully obvious dramatic irony to questions that are never explicitly answered.

The result is a well-told mystery story in a well-constructed and interesting world. It does nothing new with the idea of perfume in fiction, but the story is well-constructed and twisty and the characters are delightful.

A clever, fun, and deeply satisfying read.