Perfume: The Story of a Murderer by Patrick Süskind Book Review

Set in sixteenth-century France, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer follows a horrible little creep called Jean-Baptiste Grenouille from womb to tomb. His mission in life is to create the most perfect perfume ever to have existed, and he’ll do anything it takes to fulfill his vision.

Murder ensues.

I don’t think that really counts as a spoiler if you’ve read the title of the book.

Before I get into the contents of Patrick Süskind’s 1985 novel, I must say: I’ve scarcely seen a book with as many different front covers as this one. I mean, look at this:

That’s a ridiculous quantity of official covers. (So many, in fact, that I couldn’t decide on one to feature in the collage for this post.) Most likely, this indicates a lot of reprints and a lot of designer interest in the story. This is a very popular modern classic of a novel.

And that’s just the canonical English language print covers. I’m not even going to try to account for audiobook covers, movie covers, soundtrack CD covers, all the covers in the original German and in other languages, or the surprising number of fan-designed book covers out there.

Okay, I lied, I’m going to share one fan cover because it’s my favorite cover for the book by far. Take a look at this gorgeous gilt design by Caroline Bogo:

Isn’t that gorgeous?

Anyway.

Something about this feels like a twisted sort of Christ allegory in reverse. In fact, everything about Perfume: The Story of a Murderer makes me think Grenouille is supposed to be the actual Antichrist — or at least some demonic Antichrist prototype. It’s very apparent from the very beginning something is supernaturally wrong with the boy. Everyone who meets him feels like they’ve seen something cursed, like they need to wash their hands. He displays psychopathic behavior and creeps everyone out. He has abilities beyond what’s possible for a human.

And, most notably: Grenouille doesn’t have a smell. Not as a baby, not as a child, not as a teen nor as a man. This guy goes without bathing for years and he simply doesn’t smell like anything. Not like skin, not like sweat, nothing.

Ironically enough for someone who smells nothing, Grenouille is obsessed with scent, and his sense of smell is incredible. He can smell a specific person — or their absence — somewhere in a city while standing outside its gates. He can smell what’s behind cabinets and walls — not just obvious things like fragrance materials, but things like money, too. He can smell people and places and things to a degree that no human ever could, and this ability is at the center of his life’s obsession.

Grenouille spends his childhood learning all the different smells in the world and their names. He then devises numerous crafty ways to move forward towards a proper perfumery career that gives him access to high-quality materials. Working in a French perfumer’s laboratory, he invents the most incredible perfumes to man, pouring them straight out of his mind. Once he learns to write formulas, he doesn’t even need to test them himself: he just writes down the proportions of ingredients for an incredible perfume from his mind and moves on to the next.

Our protagonist is brilliant. Every other perfume is child’s play in the face of his talent. He can have all the money and fame that’s out there in the world for a perfumer.

But he isn’t happy with that. Grenouille dreams of far better and more powerful perfumes than those he can make in any perfumer’s shop. There are scents in his mind that he can’t express with the plant and animal notes available to him. He dreams of the perfect scent, the best perfume known to man, something that can make people love and respect him — not just for his skill in creating the scent, but in an instant merely upon smelling it.

Our hero continues being a crafty psychopathic little creep as he continues towards his goal of crafting this perfect perfume. Things take a turn when one day he smells a hint of the most heavenly scent, exactly what he needs for his concoction. He turns around the corner of a wall and finds that it’s the scent of a prepubescent girl.

What follows is the story of Grenouille going around killing beautiful young women and girls and learning to distill the smell of their sweat into perfume.

(I don’t feel like saying that is a huge spoiler considering the title of the book.)

As an aside: what’s with the “beautiful young girl whose sweat smells so good it overwhelms people with love, adoration, and carnal desire” trope? I first ran into this in Kathleen Tessaro’s novel The Scent Collector, but it’s apparent she wasn’t the first to the idea, and she probably won’t be the last.

I mean, I get it. People smell good. The skin and sweat of certain people can smell good.

But, crucially, which humans smell good to you is a very subjective thing. Consider the research in which participants smelled the sweaty shirts of members of the opposite sex and rated the attractiveness of these smells. People were more likely to enjoy the smell of individuals whose immune system genetics (the major histocompatibility complex, or MHC) are significantly different from their own. (The theory is that the “opposites attract” nature of immune systems in mate selection provides a stronger combined immune system for any biological offspring).

Even when we’re not talking about the smell of sweat, fragrance is, and will always be, extremely subjective for physical reasons, let alone the many mental ones. According to 2001 research from Bern University in Switzerland, the specific arrangement of your MHC correlates heavily with how you feel about standard perfume notes like jasmine and musk, both on yourself and on a potential mate. In the industry, we often call this skin chemistry, or simply personal preference, but science indicates it’s technically your genome that determines these preferences, likely due to facets of these notes that are similar or dissimilar to the smell of another human.

Anyway. My point is that it’s always going to be highly individual whose sweat you like smelling (and what perfumes you like smelling generally). Whether or not murder is involved, there’s never going to be a fragrance that is universally liked by people and can manipulate all of them to any extent. Scent is incredibly personal, and our preferences vary wildly based on genetic differences.

This trope isn’t realistic or based in fact. It’s an interesting idea to base a story on, but that’s it.

Furthermore, why is it extremely beautiful young women and girls, frequently described as virginal and pure, that always wield this power? I would like the read a book where the people with divine, captivating sweat are exclusively warty green-eyed men over the age of eighty.

But that wouldn’t have made as captivating of a story. The romanticized thrill of violence against women, especially young, beautiful, “pure” women, is what gives Perfume: The Story of a Murderer much of its punch. It seems that as a culture we love watching beautiful women die. (Just look at the entire horror film genre.)

And so, absolutely inane tropes are born to justify the raw sexual magnetism of young girls in media.

Like this one: the beautiful girl with magical sweat. It’s entirely ridiculous if you think about it for even a second, but much of the magic of Perfume: The Story of a Murderer lies in making it sound like it makes sense.

This is a great example of making up the particular magic in your fantasy world and working with it in a matter-of-fact manner, never drawing attention to the fact it’s absolutely nonsensical, just quietly building a world of people and choices around it. The concept at the core of this novel is ridiculous and objectifying, but accepting it as truth within this universe is what makes the whole book tick. Everything operates on this principle, making Perfume: The Story of a Murderer an absolutely horrible “…was if?” sort of book.

This is true down to the very end of the novel, which follows a frankly brilliant series of twists and turns. Each one of these punched me in the gut, being so ridiculous I almost laughed. It’s not quite as bad as, but a little akin to an alien spaceship coming down at the end of the book and kidnapping Grenouille to make perfume for them on their home planet. It’s just as fantastical, but makes sense within the magic system subtly set up by the novel.

The last few chapters are an incredibly quick ride through a series of shocking turns that left me sitting with the book in my hands, reeling with whiplash. “What the hell did I just read?” I asked myself.

All things considered, this is a great way to construct an ending. The middle of Perfume: The Story of a Murderer is a bit of a distended lull, a slow and quiet place where not much happens for a long time. The first few chapters are rather fast-paced in their expositionary romp through Grenouille’s childhood, and the last few are incredibly quick and full of plot, but the middle of the book sags a little, wandering at times away from Grenouille’s singular purpose. All of a sudden, though, just as you’re thinking the charm of the beginning is gone, Süskind snaps you out of it with a series of ending events that makes your head spin. I won’t say anything more about it.

It was horrific and disturbing and grotesque, and in spite of the way it made me feel extremely ill, it was one of the best endings I have ever read. This whole book is quite off-putting and disquieting to read, and yet I have to admit the winding construction of the plot is powerful. It feels simple enough, and yet events are mapped out with such brilliance and then filled in with such color and determination that Perfume: The Story of a Murderer comes off as something sublime and entirely unique. The way it plods and then races on to its apotheosis feels like the stuff of legends, the stuff of gods.

It has all the grand flourishes of a Christ allegory while being about one of the most disgusting protagonists I have ever seen in my life. It’s an extraordinarily confusing and distressing experience trying to assess this plot, which so beautifully comes together to tell such a uniquely revolting story.

The treatment of scent in Perfume: The Story of a Murderer is a delightful bit of fantasy. Like Erica Bauermeister’s The Scent Keeper, this is a book that leans into the power fragrance has to manipulate people’s emotions and thus alter their actions. Where The Scent Keeper is subtle and plausible, however, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer is grandiose and fantastical. The impact of scent is portrayed as so profound and inherent that it’s as if humans are just another animal reacting in primal, unthinking ways to the pheromones around us. (Whether humans have pheromones, and the capacity to perceive them, is still not scientifically proven. But that’s a debate for another time.)

Any idea of objective reasoning goes out the window as people in Perfume: The Story of a Murderer do unthinkable things on the instantaneous basis of smell alone. This is the element that makes Perfume feel like an odd fantasy novel set in pre-revolutionary France. There’s just not enough scientific backing for this to feel like sci-fi. Rather, there’s a certain magical element and suspension of disbelief that’s necessary for this story to work. It investigates an impossible extreme of a fascinating concept — controlling people through scent — and its go-big-or-go-home nature is what makes this a fascinating story.

I really like the historical tone of Perfume: The Story of a Murderer. The details of worldbuilding are consistently excellent. The disgusting portrayal of the foul streets of Paris, the portrayal of the fashions and customs of the day, the masses of different people with very French names entering and exiting the story in passing never to be mentioned again… It feels like I’m reading Victor Hugo.

The third-person narrator’s voice, too, is one of the best qualities of the book. It mostly stays out of the way of the story, but is matter-of-fact in the sort of dryly amusing way that makes it feel as if some concept, perhaps death itself, is telling the story rather than any human. The brief detours along the lines of “We’ll never see this character again, so let me quickly tell you how they died” are frustrating in the pointless and abrupt ways countless one-off characters’ lives end, but something about their presentation is also rather amusing. The ironies in each one really make the whole book great fodder for an Alanis Morissette song.

I don’t think the point of the story is to ask the question of whether perfect art is worth human lives. To Grenouille, it’s no question that they are. To the reader, it’s probably apparent that they’re not.

(I mean, if you have to make perfume out of people, at least get their consent beforehand and wait for them to die of natural causes. Maybe make it a box you can tick on your driver’s license, like being an organ donor.)

There’s no philosophical treatise here, just a fascinating and well-woven story about a very screwed up, vaguely-Antichrist-coded little freak of a man.

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer reminds me, in many ways, of Robert A. Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land. Both books follow a very strange sort of Christ figure through rather similar arcs that coincidentally come to a very similar end. Both of these figures have a very unusual perception of the world, and their pursuit of the ideals that arise from this perception becomes the driving force behind the plot of the story. Both are stuffed full of fascinating new ideas and some of the most atrocious and unpleasant literary treatment of women I’ve ever had the displeasure of enduring.

By the way, when I saw this book was about a murderer, and all the imagery of a single red-haired girl on most of the covers and in most of the movie stills, I assumed this was about one murder. Maybe a few. It turns out I was not even remotely correct. I very loosely kept count, and Grenouille killed at least at least twenty-seven women that are mentioned in the narrative. That’s assuming there were no incidental additional murders required for covering up the others, which is not a given, as Grenouille muses in relief at one point that there was no maid he’d have to take out at one woman’s home. This is a mass murderer.

You can’t blame me for expecting a story detailing the profound impact of a single murder, though. Looking at any imagery about the book or movie, all you see is pictures of one beautiful red-haired girl. The victims in Perfume: The Story of a Murderer are not people. Told through the eyes of the murderer himself — and occasionally through those of other men around the woman, whose only observations are crudely and sometimes incestuously lustful — the women are objects of beauty and nothing more. They all blend into one amalgamation, both literally in the bottling of their mixed essences and in the narrative’s treatment of them as a muddled set of near-identical objects without names or faces.

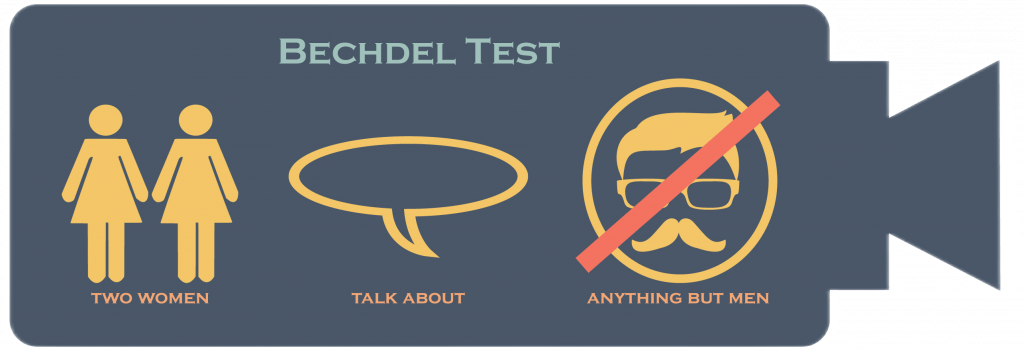

No way in hell does this book pass the Bechdel test. Which isn’t something you have to care about, I suppose, but it’s a good thing to know going in: this story has no women in it. Absolutely none. Incidental mothers, wives, and nuns float in the background in single-sentence references. The “virgins” are treated as sex objects and possessions, nothing more.

Sure, there’s lots of art out there that’s good in some sense of being interesting or original or thought-provoking while also portraying nothing but romanticized sexism and dramatized violence towards women. But those stories are most likely not going to be enjoyable for your average female reader. It’s understandable that they’d feel rather upsetting to many.

I’m a strong proponent of talking about this as a valid reason to dislike or avoid certain media. I don’t have to like a book or movie just because it’s a classic when all I see in it is disgusting exploitation of, or violence towards, women. It’s okay for that to feel deeply upsetting to read. It’s absolutely okay to dislike a piece of media for that reason.

Art is about how it makes you feel, and if you don’t like it, you don’t like it. Sure, things can be thought-provoking while being uncomfortable, but cultivating one’s own experience of art and media means it’s entirely valid to say you dislike something because the violence towards women — or another form of exploitation towards some group — made it a deeply unpleasant experience for you.

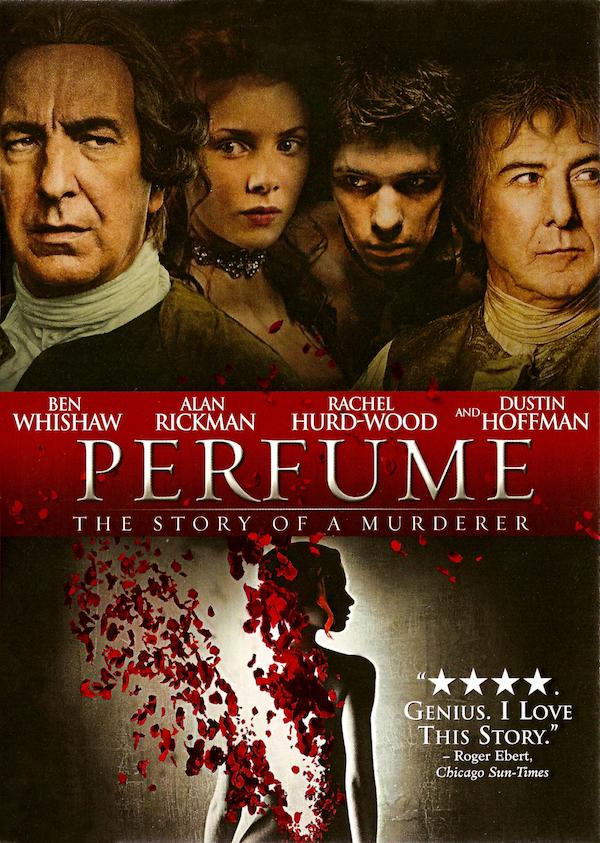

Before reading Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, I expected I could read the book and then dutifully proceed to watch the movie — I was raised to always read the book first — and review both. However, I don’t know that I’m ever going to review the movie, no matter how many people might have an interest in that blog post. This book was simply horrible and disturbing enough on paper, and I have absolutely no desire to see it on the big screen.

I don’t know what this story gains from being transformed into film. There’s nothing here that I feel needs to be demonstrated visually in order to make a full impact. This isn’t a book about a painter or a dancer; it’s about a perfumer, and we don’t get a richer experience of the art by looking at it visually. If anything, I would imagine film robs this story of the opportunity to describe so many scents in detail, taking away the crucial approximation of the perfumer’s art conveyed on the page.

Doubtless, the movie lets the story reach a larger audience. But I think what really makes this story well-suited for a successful movie is the subject matter: the objectification and brutal murder of beguiling young women.

Cinema presents a greater opportunity to exploit imagery of beautiful women meeting a horrifying end. That’s an idea that makes me even more uncomfortable than reading the book itself: the fact that this is a great candidate for a movie remake because it’s full of hot girls who die gruesome deaths. That this subject matter is what makes this story so popular.

Horror and gore cinema generally are sexualized enough as it is. I have no desire to see that medium unleashed onto a book that’s all about killing “beautiful young virgins” from the murderer’s perspective.

That’s a decision based on a deep personal aversion and revulsion. I won’t speculate any more about the movie here because I haven’t seen it aside from some clips and trailers, and as of this writing do not intend to. The story was interesting and original, and I don’t think I’ll gain anything by watching the movie. If anything, there are crucial elements of the book that don’t easily translate to cinema. And, to be honest, I don’t feel like sitting through several visual hours of romanticized murder of beautiful women.

Yes, I’d call it romanticized. The fact that only the sweat of the most beautiful and desired girls and young women is good enough for Grenouille makes that almost inevitable. The storytelling exclusively through men’s eyes seals the deal. All the sorrow we see about the women’s deaths is about the loss of their beauty in this world or the loss of the opportunity to sleep with them. Grenouille himself is rather systematic and matter-of-fact about the process of killing the women, relishing only their scent. The narrative, however, embraces a public obsession with women as objects of beauty and sex appeal instead of people.

One could argue this is the only way to tell this story. It’s centered on a mass murderer and a bunch of men in sixteenth-century France. What could you expect? And besides, treating the women as people would feel like extraneous fat in a story that is fundamentally about women as objects. Building up profiles of the victims as humans with wants and needs and ideas simply wouldn’t make sense or be relevant. None of the narrators care about that, and it takes away from the central theme of women as objects whose power can be extracted via cold enfleurage.

Patrick Süskind has artfully composed something incredibly horrible in Perfume: The Story of a Murderer. His storytelling ability is impressive, and this certainly feels like a very original story with an immense gravity around it. It’s written like a great book, an important book, an inspiring hero’s journey, the bildungsroman of a god. And it’s about a guy who murders women and bottles their scent. Pulling off that dichotomy takes immense skill. Hats off to Süskind.

But reading (and watching) the disturbing isn’t for everyone. If this doesn’t sound like something that’s worth the discomfort of reading it for you, that’s completely okay. I think I’m glad I read the book and got to appreciate the art of storytelling here, but I also never want to experience this again, especially not visually in movie form.

I will concede, though, that this is the most grandiose- and monumental-feeling fragrance novel I have read so far. This is incredibly well-written. The seemingly simple plot is presented in such a way that everything here feels entirely new.

At the same time, I have no idea whether I should call this a good book. It’s way too gross — and complicit in its own grossness — for me to give this five stars in good conscience and recommend it to my friends. The fact that the entire narrative is built on objectifying and murdering women makes this feel exploitative, even though the book is fictional. Portraying lots of innocent pretty girls coming to a horrible end is a very cheap and easy way to generate a strong emotional response from the reader, and it preys on disturbing cultural ideas.

You and I both know this book never would have taken off and received a film adaptation if instead of gorgeous women Grenouille was obsessed with killing old men, or endangered animals, or something. As a culture, we see violence against women as much more palatable and sensational than other kinds of violence. It’s every superhero’s tragic backstory, every horror movie’s graphic first death. I hate the way we love watching women die, which obviously means I’ve got a bit of a problem with Süskind’s first and most famous novel.

In short, like any perfume (or the smell of any person’s sweat), Perfume: The Story of a Murderer won’t appeal to everyone. I don’t even feel as if I can pass a general recommendation to a particular group here.

If reading this review made you want to read this book, read it. If it made you never want to read a written word again, I am sorry, and also please don’t read the book. This book made me very confused and rather speechless, which doesn’t happen often, so I’m afraid that’s all I can say.