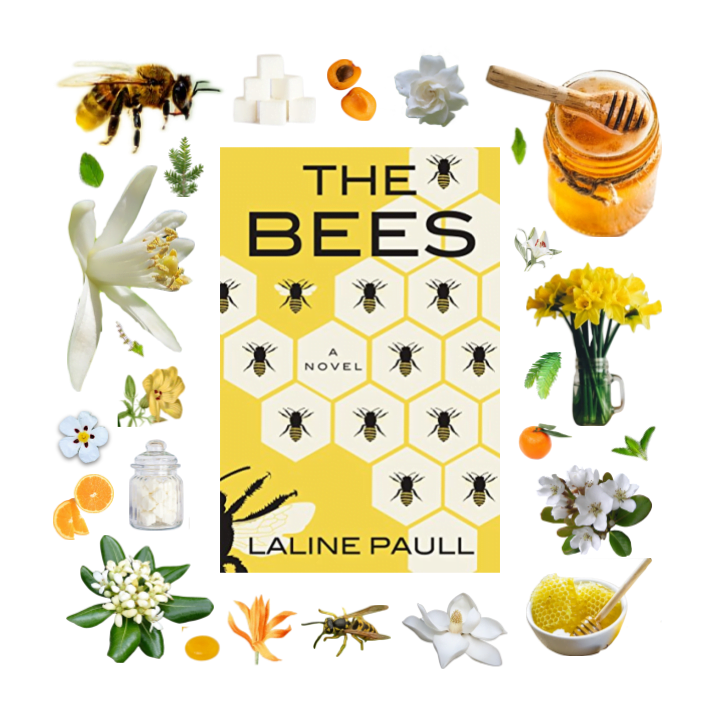

The Bees by Laline Paull Book Review

I went into this book never once suspecting it would be a groundbreaking olfactory novel worth reviewing on the blog. Nor did I expect to gobble it down over the course of a glorious two days. But life is full of such wonderful surprises, isn’t it?

The Bees by Laline Paull is a book I’d absentmindedly ordered from the library when I saw it listed in an article about books narrated by a plural entity. (For the record, it was a bit of a misleading listicle; the third-person-plural thing only happened a couple of times throughout the book, and it was less of a narration and more of a brief shift in perspective.)

“That looks interesting,” I thought. “A book about bees, narrated by bees. Huh. And no queue at the library. Alright, let’s see what this is all about.”

I then proceeded to forget about the book and renew it several times before finally diving in. And wow, am I glad I did.

This is a stunning novel that does groundbreaking things in so many different realms of fiction writing. It does things with the ideas of self, class, individuality, belonging, and voice, with religion, with communication, with the value of a life, with love, that I’ve never seen before.

And, perhaps most relevantly here, it does fascinating things with scent.

The Bees follows a single bee named Flora 717 from hatching in her beehive all the way through to ripe old bee age. The book isn’t driven by a clear overarching quest to accomplish as much as by a gripping combination of exploring this unique world and surviving terrifying new day-to-day encounters.

Of course, by the end, a clear overarching plot emerges with dire consequences for the hive, but for more than half of the book we focus on the development of Flora 717 and explore her world around with her, stopping only occasionally to examine a curious piece of foreshadowing.

This is a setup that does have the potential to get aimless and dull. But this is not the case here. The world of The Bees is so unique in fiction, so entirely new and strange, and the day-to-day activities of Flora 717 are all breathless perilous adventures. Exploring this wonderful new world through the eyes of a new bee is an utter joy, dotted with moments of absolute horror, of abject terror and then relief.

I think this effect is largely accomplished by:

1. Our implicit understanding that bees do not live very long, and each day could be Flora’s last.

2. The sheer quantity of dead bees in this book.

Yes, bees are contantly dying all sorts of unique new deaths in this book. I hate the constant intense grieving mood this sort of thing usually creates in books about humans, but the life of an individual in The Bees is given far less weight than in our world. The survival of the hive is utmost, individualism is all but nonexistent, and individual lives are worth little. Jobs and destinies are entirely assigned at birth. Males are pampered, praised, and spoiled while females do all the work. The queen is worshipped as the center of religion and life itself.

This sounds like the sort of cliche regime a mid-2010s dystopian teen novel would whip up. But author Laline Paull doesn’t treat it that way. The Bees is a fantastic philosophical exercise. It shows us a society dramatically different from ours, fundamentally anti-individualist with a literal hive mind and an intricate caste system of assigned roles.

But instead of showing our main character as some insolent teen who’s here to take down the system for the good of the individual, she shows us the other side of it. The senses of both obligation and genuine comfort and joy in the hive. The sweet, life-sustaining nectar of the Queen’s love, which flows through the bees to their elation and forms the basis of the hive’s fascinating religion.

This is not me saying our own human society should abandon any sense of the individual and begin worshipping a goddess queen while we do the work we were assigned at birth until we are no longer useful. Oh no.

But it’s so refreshing to see an exploration of a society so violently different from hours in fiction without a heavy-handed “we need to change this immediately” narrative.

Sure, there are plenty of things about the system that put Flora 717 in contant danger, that hurt her, that would throw her life away in an instant, that cause her daily problems. But there are also things about it that bring her immeasurable comfort and joy. You don’t need to overthrow a regime for a fictional exploration of it to be fascinating and worthwhile. Especially when it’s shelled in the comforting abstraction that these are bees and not humans, and that biologically they tend to be that way, while we tend to be this way, and this is how they survive.

This world is full of wonders. One of them is the many ways the bees communicate. They have language which is assumed to be spoken language — though who’s to say whether the scribbles I’m reading and interpreting on the page might actually represent smells, or movements, or something else entirely to the fictional bees. There’s an ancient language shared among all insects and arachnids. And there’s a tongue specific to the bees, as well as an accent or perhaps even a dialect exclusive to just the bees in this hive.

In addition to what I assume is spoken language, however, the bees communicate in other ways I’ve hardly seen explored before. Much of the way they percieve and convey information is encoded into movements, smells, and touch.

The bees dance to show each other the way to the flowers. They beam their thoughts out around them via their antennae, which they can touch together to transmit information. They can try to close off the space around their thoughts, and they can pry one another’s open. They step on different panels and codes in the hive to recieve directions and instructions. They have a system of bells and a calendar of sunrises.

And… they use scent. A lot.

Scent is used by the bees to communicate in ways I wouldn’t have thought possible to write about effectively. It’s the language that forms the basis for their religion and societal structure. It conveys their emotions to others and can be used to manipulate their emotions in turn.

One of my favorite unique communication inventions in The Bees is the queen’s library. It’s a collection of what seem to be six fine images (or perhaps codes?) in panels of her chamber walls. Each one tells a story — that is, it trasports any bee who dares come close and touch it into a world that feels entirely real, experiencing the story as if in a dream.

It’s not entirely clear what the mechanics of the story panels are. But I think it makes sense to assume much of it comes down to scent. It’s so much of how the bees communicate, after all, and the stories are told in a way that is incredibly immersive and emotional. Only a scent can transport you to another place so completely in an instant.

The “scents can dramatically manipulate people’s emotions” theme is certainly common in the microgenre I’ve come to lovingly refer to as olfactory novels. These are books that heavily feature scent, and utilize it in storytelling in ways I find unusual, noteworthy, or novel.

We’ve seen it in The Scent Keeper by Erica Bauermeister, with its marketing company manipulating shoppers via subtle piped-in room scents.

So, too, we’ve seen the theme to a lesser extent in The Perfume Collector by Kathleen Tessaro, where scents and perfumers are entangled in dynamics of power, of manipulation and out-manipulation, of pleading from beyond the grave and unlocking dusty memories.

And we’ve definitely seen it in Perfume: The Story of a Murderer by Patrick Süskind, whose ending is the most dramatic, artistic, astonishing execution of this concept I’ve ever seen.

In terms of sheer originality, though, The Bees takes the cake.

Here, scent is used in day-to-day communication in ways that I’ve never even seen suggested in stories about people. It’s fascinating and new and I consumed it with a ravenous pleasure, but it’s also good, hearty, salubrious food for thought.

All of these books make me, as a self-ascribed fragrance person, examine the relationship between myself, scents, and the world in an entirely different light. In many ways, however, The Bees goes the farthest, suggesting the wildest sorts of possibilities I’d scarcely have ever thought of myself.

Scent as manipulation is frequently explored in fiction; scent as expression is less so. What can the way I smell convey about me — not just about my personality, but my emotional state, my background, where I’m going, what I’m doing, what my hopes are?

This is about more than just perfume, too. There’s so much we can learn about others and the world with our noses, and yet as humans we scarcely recognize or appreciate this fact.

It’s kind of like how, when you meet a new person, the first place you look isn’t usually their face — it’s their hands. Your body is checking for danger, evaluating their stance and looking whether they might have something hazardous with them. We feel safer when we see people’s hands in front of them instead of being hidden.

Is it really a coincidence that hands are put up in surrender, that it’s rude to have your hands in your pockets when talking to someone, that we shake hands upon meeting a new acquaintance?

And yet it’s a system we don’t often think about. The same goes with the ways we use scent to convey and understand information. I challenge you to reflect on what sorts of emotions scent cues triggered for you today, and what you learned or assumed about other people by smell.

And what is it, do you think, that your scent says about you? This isn’t a trite Buzzfeed quiz question, and it also isn’t restricted to perfume. Running into someone that smells heavily of soap, of sweat, of warm baked goods, of advanced age, of campfire smoke, of cooking accident smoke, of cold air, of hair gel — what do you learn or assume about them from that? And what might people be learning or assuming from you?

The question of whether or not human pheromones exist, and whether or not we’re currently equipped with organs to decode them, remains debatable. (You’d be forgiven for thinking otherwise, given the sheer brute force of the marketing push behind so-called pheromone-based fragrances that promise to win over friends and lovers left and right.) But even without them, there’s so much information we exchange through scent without realizing it.

The world of The Bees is perilous at every corner and full of unending labor, but it’s also so delicious I want to experience it for myself. There’s pleasure and delight and genuine religious ecstasy and so many wonderful kinds of love explored here. Somehow, a book so littered with dead bees still manages to be sweet as honey.

This book is completely unlike anything I’ve ever read before, and it’s also simply a pleasure to enjoy. This isn’t a doom-and-gloom sort of book that feels like something heavy you ate at dinner sitting in your stomach as you watch the protagonist struggle to survive. it’s an adventure with plenty of luck, glory, and love laced through it.

And what more could you want of an adventure novel, really?

The Bees by Laline Paull is a joy. It presents the reader with a world unlike anything you’ve ever seen before and a society that’s likely radically different from your own. It guides you as you explore this strange new world like a newly-hatched bee yourself, learning instinctively to learn and understand senses and behaviors you didn’t realize you had in you.

And you speak, and you sing, and you fly, and you dance, and you smell.

Absolutely delightful.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to bathe in Zoologist’s Bee Extrait de Parfum and dream of flowers and honeycomb.

One thought on “The Bees by Laline Paull Book Review”