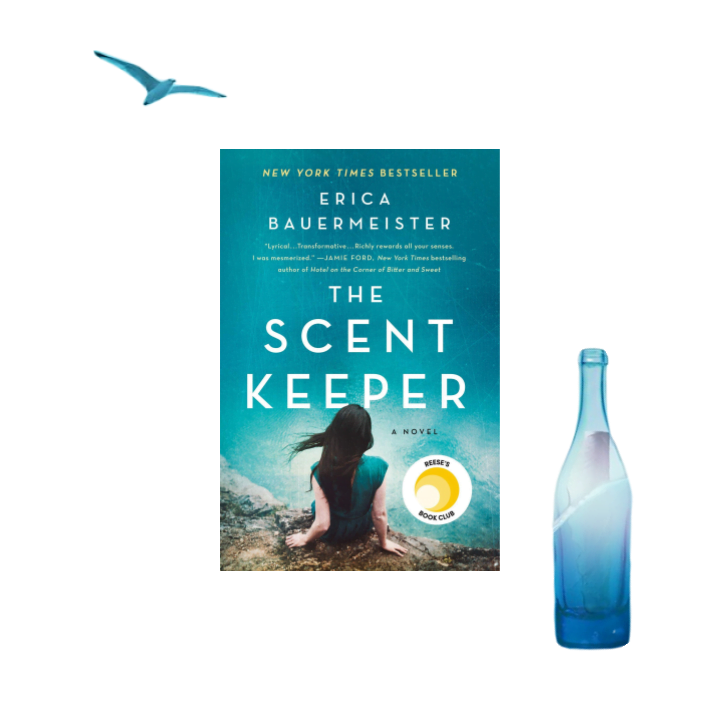

The Scent Keeper by Erica Bauermeister Book Review

They say not to judge a book by its cover, but of course everyone does. Looking at the cover of The Scent Keeper by Erica Bauermeister, I expected something childlike and full of self-reflection, perhaps ponderous at times in its staring off into the faraway sea.

I did not expect a masterclass in how to make your readers feel pain.

Indeed, unexpectedly, this was one of the most emotionally painful books I have ever read.

Many novels try to be extraordinarily sad. They choose a grotesque piece of explicitly miserable subject matter and dive in head-first. Too often, there’s an overbearing bumptious tone that brings to mind the horrendously scripted infomercials at the heart of the war on drugs, the author relishing their role in bringing awareness to whatever pit of human misery they’ve chosen to exploit.

On the surface, it works. These books rack up best-seller weeks and awards like a helicopter parent hoards their child’s every piece of elementary school homework and hideous macaroni art. Teenagers run around sobbing and declaring that this is their new favorite book, smiling smugly as certain literary adults applaud their maturity for bravely loving something so very sad.

But this isn’t the way to write a book that really tears people apart. Readers of the run-of-the-mill tragedy-exploitation New York Times bestseller are plunged into a shockingly cold pool of misery and are numbed too quickly in order to cope. How else can they keep telling everyone how much they love this book and how important and sophisticated it is?

No, writing a book that really hurts the whole way through requires restraint. A book that delivers prolonged pain can’t be centered around some edgy high-concept image of some problem in modern society. The tragic thing can’t be explainable in a few words. On the surface, things need to be alright. There needs to be subtlety, with hope and love the whole way through. Then you need to write in progressive doses of devastation from honest mistakes, from miscommunication, from characters trying their best and that still not being enough. That steady drip of heartache that’s just a bit bigger than quotidian is what really tears your readers apart in time without exhausting their emotions.

And this is exactly what The Scent Keeper does.

True to some of my impressions of the cover, The Scent Keeper is presented through the eyes of a child, and, unlike some self-important tragedy novels, is truly framed in the broad strokes of wonder and love essential at the heart of a child’s worldview. The narrative voice is childlike but not childish. As narrator Emmeline grows up from age four to seventeen, she gradually stops believing in some things: mermaids, fairy tales, and that everyone will be kind or has her best interests at heart. However, she never questions that there are people who love her and care for her, and this keeps her narrative from descending entirely into the hopeless depths of misery.

Even in the most heartbreaking moments, Emmeline moves forward, never stopping to immerse the reader entirely in the still water of her grief. But that constant movement and that faint steady drip of wild, desperate survivalist hope and unquestioned love are like foils to the sadness, accenting it further as our heroine refuses to stop and let it fully sink into her.

The sadness of The Scent Keeper is frustrating and at times infuriating in the same way that movie plots based entirely on miscommunication can be. Emmeline weathers and witnesses wave after wave of pain through events common enough for you to know someone who has experienced each.

The Scent Keeper is not written with a pompous lesson about misery at its center, so I hadn’t been prepared for the heartbreak of feeling and witnessing this sheer amount of casual everyday grief and fear. Reading the novel, you are a determined, hardened survivor child, entirely alone with no one there to witness the deepest parts of you. You experience or witness countless waves of earth-shattering events and it feels as if with your every choice, things are slipping farther and farther out of your grasp.

With the turn of every page, you discover something new with the naïvety of a child who thinks she has felt every pain, but actually hasn’t felt this one before: grief, loneliness, the loss of relatives and pets, bullying, isolation, sexual harassment, cycles of abuse, being perpetually misunderstood, the risk of starvation (both in the wild form of winter and in the civilized form of poverty), romantic heartbreak, being forgotten, being exploited, hurting and disappointing one’s parent figures, commodifying one’s talents into devious consumer products to survive, and the progressive loss of innocence and hope that runs through all these events hit you like it’s your first time learning about each one.

Emmeline is a survivor who is always moving forward, but she is also a child, and, though she never stops to wallow in any of this, the agony of discovering a new way life can hurt is tangible through the page.

I had to put this book down a number of times just because it hurt too much and had already ruined my mood for the day and I couldn’t take any more. Reading The Scent Keeper contributed to the sort of dark, moody, silent feeling you have when you’ve been inside all day for several days in a row, haven’t talked to anyone, feel a bit too nauseous to really eat whole meals, you’ve been staring at screens entirely too long, and your whole brain feels fuzzy and hollow.

Each time I dreaded picking the book back up, knowing more of the same pain was in store. With each wave being a new dull sublunary heartbreak, I never got used to it, never adjusted in a way that made it hurt any less as things continued to go wrong and spiral out of Emmeline’s hands. Perhaps the worst part is the way the narrator blames herself for almost all of these tragedies, not in a wallowing self-pitying teenage way, but in a private perception of fact she shares with no one. At each and every turn she makes the best choices she can in the circumstances, doing what she thinks is the right thing for her and the people she loves, and yet it seems that despite her best intentions things always go horribly wrong.

Though she keeps going, there’s a heavy lodestone of grief, guilt, and helplessness that follows her around in the form of things she tells no one and tragedies where she unquestioningly blames herself. This, combined with a streak of miscommunication plot here and there in her disconnection from the people she loves most, makes for a frustrating, infuriating sort of misery that’s sure to ruin your day.

Another compelling component of the deep sadness of The Scent Keeper is a kind of miserable half-sighted dramatic irony. With every one of Emmeline’s conflicted, hard-to-understand choices for survival, you’re left yelling “No! Don’t do it!” at the page while simultaneously lost for words as to what else she should do.

There’s always a creeping horrible feeling that this choice that Emmeline thinks is the best chance she has is going to lead to more terrible things, and yet you can’t fault her for it because she’s a child and you can’t think of any better ideas yourself. It’s a terrible feeling of being stuck with this character in this situation, pressed by each new development into the best of an array of lousy choices.

Maybe I’m just sensitive, but I really don’t usually react to books like this. I hesitate to recommend The Scent Keeper for precisely this unexpected, unpretentious, mundane sea of new heartbreaks and miseries that dominates the novel. Sure, in the last few chapters things lighten up a little bit, letting hope and some small victories shine through and providing some much-needed relief, but the first four fifths of the book at least are an overwhelmingly gut-wrenching experience. The Scent Keeper is well-written and takes place in an interesting and beautiful world, so if you’re one of those people who seeks out and relishes literary misery, I recommend it full-heartedly. If that pain sounds like too much to bear, I’d skip this one.

The world of The Scent Keeper is beautiful, viewed through the eyes of a child who, through it all, pays attention to and appreciates all of her senses. There are strange and gorgeous things in the wilderness of the island, in the small town living of the cove, in the sparkling consumerist wonders of the city. There’s a sparkling magic that permeates every place. Reading about the cove makes me think of a 2,000-piece jigsaw puzzle of Cinque Terre I completed in high school, all exaggerated bright neon-colored buildings against a dusky background.

The cove feels more daylit and cozy in its provincial fishing-village charm, but something about the way all the colors and tastes and smells are heightened with childlike wonder reminds me of the colors here.

In all these places, there is a survivalist sense of adventure in escaping the ever-lengthening list of past traumas chasing after Emmeline.

There is beauty in the steady ribbon of unquestioned love running through most of her life. A number of caring parent figures relate to Emmeline and comfort her in different ways, such that she has scarcely questioned that they truly love her. The painting of a building lifelong friendship and burgeoning romantic connection is also a joy to behold. Though there’s a too-grown-up and at times bitter element of trauma bonding holding the two together, there is also tenderness and genuine appreciation for what they have to teach one another.

As with all the other masterful flourishes of this story, Bauermeister exercises impressive restraint here. The result is an innocent and childlike exploration of partnership that manages to avoid wandering into any hokey teenage-romance territory. It provides a thread of desperately-needed relief at times throughout the novel, while also bringing along its own requisite truckload of pain through arguments and conflicts, inability to share secrets, perceived rejection, watching one another’s heartbreaking life events unfold, and the searing ache of seeing caustic traits show up in someone you care for.

Nonetheless, this is a relationship that ultimately brings hints of hope and excitement to Emmeline and the reader, and Bauermeister’s less-is-more approach is what makes this so genuine. There are maybe two or three sentences clearly acknowledging the romance in the novel, and they’re burned in my memory for the subtle way they convey comfort, safety, and warmth that is sorely needed in this landscape of everyday agony.

The characters in The Scent Keeper are all archetypal but well-drawn. Each is a stock character you’ve seen before: the sweet old small town couple, the busy businesswoman, the gentle father with dark secrets raising his child alone on books, the surviving child, the power-wielding male school bully, each member of the family caught in the cycle of abuse, the selfie-taking tourist, the teachers who are nice but not kind, and so on. Each person and place draws on things you’ve seen before, but is colored in with a distinct voice shaped by fairytale wonder.

Reading the first few chapters, in fact, when Emmeline is still quite young and her life and conversation are dominated by a belief in magic and fairytales, I was rather convinced this was going to be a fantasy book, in a world where magic is real — so many things seemed unexplainable, after all, if not for magic. Bauermeister masterfully draws you into Emmeline’s worldview through the use of the first person, such that, in the first chapters, things only make sense through a fantasy lens, and you genuinely can’t think of any other way for these things to be logical if not for magic.

In time, as Emmeline gets older, the belief in magic is shaken off until it is apparent this is a realistic fiction book with no magical elements, and yet a certain texture remains in your perception of this strange realistic world. Everything is colorful and beautiful in a very particular way, drawing on archetypes to form the general shapes while the languages focuses on coloring them in with simple descriptions of beautiful and painful things.

Many books where a number of horrible and traumatic things happen to the protagonist as they keep fighting to accomplish their goals — coincidentally, often in the fantasy genre — are saved by a feeling of Pyrrhic victory in the end. Sure, all those awful things happened to me, the protagonist seems to think, but if they hadn’t, I wouldn’t have been able to save the world and learn valuable things in the end, and so everything happens for a reason.

The Scent Keeper does manage to scrape an ending with happy and hopeful elements, but it hardly accomplishes any such sense of justification in the pain. In a way, this is a relief: in life, after all, not everything happens for a reason, and many horrible things happen for no good reason at all. Forming these into a narrative of learning and growth can be helpful, but the fact remains that you could have had a perfectly good and happy life without the awful thing happening to you, and whatever you learned in the process isn’t necessarily a lesson worth the trauma of the event.

This is The Scent Keeper’s cruel last dose of aching sadness: tragedy does not have a point. The people who were hurt did not have to be hurt for Emmeline to find a happy ending. Things just happened that way, and she (and we) are tasked with picking up the pieces and carrying on without pondering too long what could have been.

There are elements of The Scent Keeper that are left unexplored in the end, threads you might have expected to get picked back up that didn’t. The ending is rather abrupt, leaving the reader with the suggestion that finally, a series of good things happen next, but not staying to show them to you. On one hand, this abruptness is frustrating: I have stuck with Emmeline through so much pain, and now that it finally seems like things are going to be alright, I don’t get to know what happens? But, on the other hand, endings are a delicate thing. Judging by the light and delicate hand in composing the rest of the novel, it makes sense that Bauermeister errs on the side of letting the reader imagine what happened next instead of overstaying and drawing out a description of the rest of Emmeline’s life.

I would be remiss not to discuss the centering of scent in this novel, the thing that drew me to reading and reviewing The Scent Keeper in the first place. If not for my love for scent, I would not have been drawn in by The Scent Keeper’s ponderous cover and ambiguous title, nor its spot on Reese Witherspoon’s reading list.

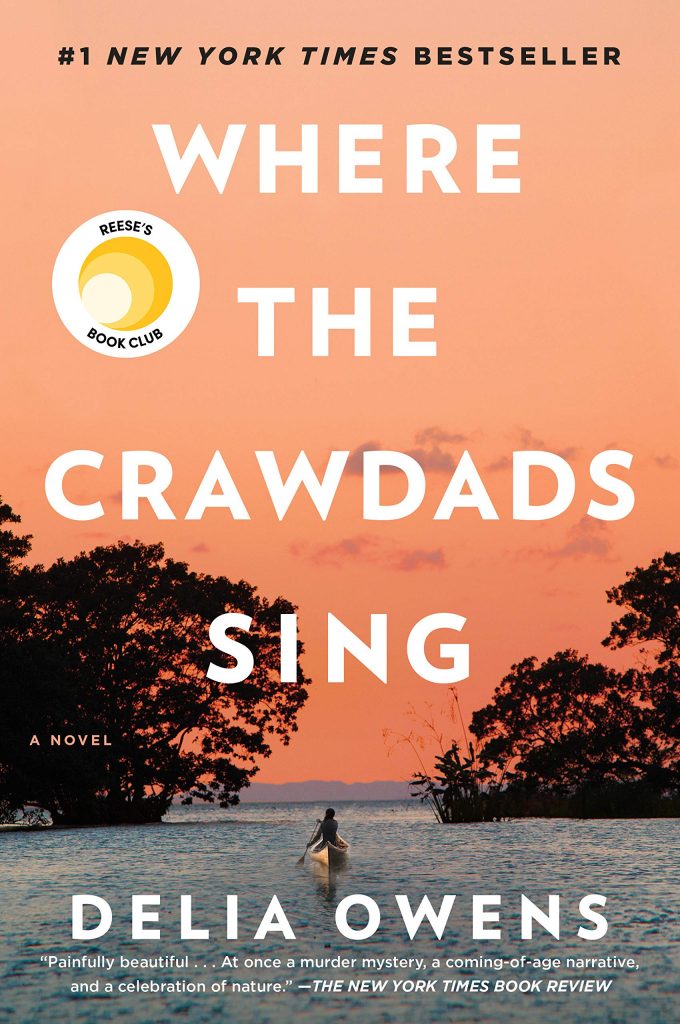

(I’ve read one Reese’s Book Club pick before, Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens. It’s another aching book about a little girl facing far too much, which the actress described as “painfully beautiful.” Witherspoon seems to have a thing for this sort of book. I found that one both less painful and less beautiful than The Scent Keeper, all things considered, and, crucially, far less interesting. Whereas The Scent Keeper kept me paying attention to its every single word — a relative rarity when zoning out from audiobooks is so easy — I didn’t care at all for the Crawdad story, its flat characters, or for its combination of overwrought language and ridiculous, contrived, vaguely classist use of inaccurate dialect. Anyway.)

The handling of scent, both in navigating the natural world by one’s nose and in the world of perfumery, is masterful and delicious to read. Baumeister clearly has the background — through research or through personal experience — to both explain particulars of the fragrance world and to describe how it feels to live by one’s sense of smell. The beautiful imagery of The Scent Keeper covers all senses, but the constant casual descriptions of various smells really shine.

It does feel like a bit of a gimmick at times, this narrative constructed around scent, carefully dropping terms in the latter half to help the reader understand the basics of perfumery, but it’s such a rarity that the exploit is well-earned. There is so much delicious imagery in fiction out there, but scent is a glorious opportunity for it that often goes unexplored. Under the excuse of the gimmick of living by one’s nose, The Scent Keeper fully embraces this opportunity to create scenes and places with one more dimension than most written worlds bother to describe.

Reading The Scent Keeper really reminds me, in a proud, desperate, aching way, what a romantic and beautiful thing it is to have a sense of smell, to pay attention to the scents around you, to intentionally enjoy the simple sensual pleasures all around us as a means of survival. It drew a breathtaking portrait of both the rampant crushing consumerism and the raw beauty in the world of creating fragrance. It struck up a new urgency in me regarding how badly I want to be not just a fragrance writer but a nose, to dive back into creating scents of my own with more knowledge, experience, and resources than I had had mixing my mother’s essential oils as a middle schooler.

It also explored ways scent can be used that I admire and hadn’t thought about much before: to find food, to read and understand people and places, to manipulate people into feeling and doing particular things. That last one is a fascinating concept explored in The Scent Keeper in a way that sometimes teeters on the brink of a kind of consumerism science fiction, a window into a fascinating world where marketing is finally fully embracing the power of scent. Sure, right now there’s new car smell and dark teenage clothing stores piped full of stifling blue cologne, but The Scent Keeper paints a fascinating picture of what this art could become when fully applied to controlling people’s behavior.

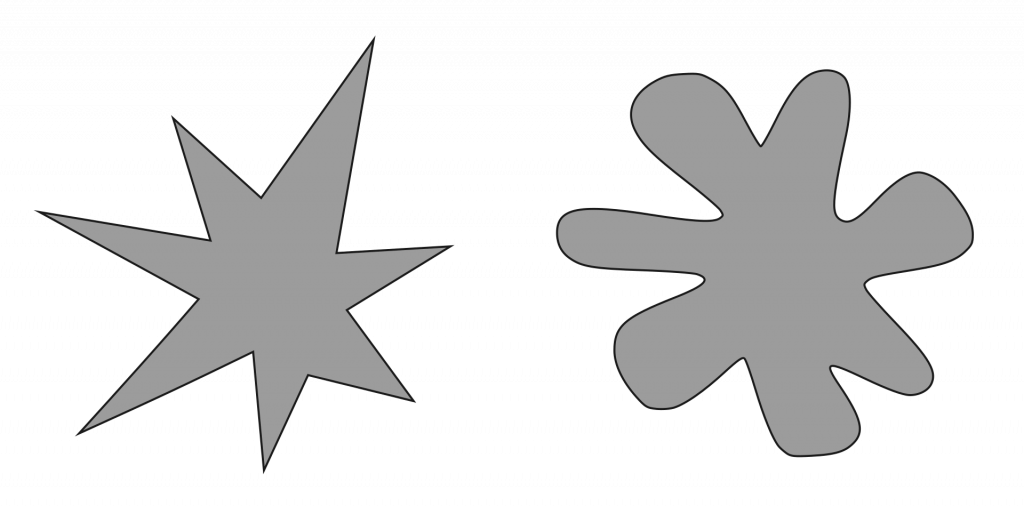

The mechanisms of this scent-based manipulation seem to rely heavily on cultural associations at first blush — but then, how much of the way we perceive fragrances emotionally is innate? Is there something in the smell of jasmine that feels like a seductive troublemaker for anyone from any culture, just like there is something about a shape called bouba that feels round and a shape called kiki that feels spiky?

This is a fascinating topic for research, but The Scent Keeper reminds me of the inevitable application of the results: a more fine-tuned art of using fragrance to make people buy stuff they don’t need.

The Scent Keeper largely keeps away from modern technology through the convenient fact that Emmeline grew up on an island and then in a small coastal town, but I wonder about the implications of market perfumery like that in The Scent Keeper in combination with other modern manipulation technologies. Though target display ads that use information about you to show you what you might like are commonplace, the world is seeing its first proxemic physical digital display boards that detect qualities of passersby (such as their gender and age) and use these to display particular messages.

I wonder how these technologies might someday capitalize on scent. The strong connection between memories and scents makes this a powerful tool. Meanwhile, certain facets of the way we as a society treat fragrance — such as the way fragrance trends tend not to cycle, making it easy to identify smells as ‘old lady’ smells because they remind us of things that were popular long ago — that would make it easy to use demographic targeting to make places smell comforting and familiar to different people.

Suffice it to say, the smell-related plot points of The Scent Keeper raise fascinating questions about the future of scent technology, making this in a way a sort of realistic near-future science fiction novel. The description and use of scent throughout the novel to color in people and places is simply delectable. The constant use of scent is masterful and light-handed, such that you hardly notice that it’s there or that this isn’t a typical dimension of description in fiction.

Even without an established interest in scents, readers are sure to come away paying more attention and appreciation to the smells around them. In fact, this is likely one of the most compelling things about the book to a non-fragrance-person audience. I adore the use of fiction as a vehicle towards a greater presence in our senses. This is something Baumeister seems to have experience with from her previous novel, The School of Essential Ingredients, which is filled with rich descriptions of tastes.

On the whole, The Scent Keeper is a book of gorgeous, lush imagery, compelling characters, and fascinating narrative voice that is just a bit too heartbreaking for me to recommend unilaterally. Sure, the ending is a happy one, but the steady drip of emotional pain taken in stride by this child is something that not everyone will find worth reading. The language keeps the reader paying rapt attention, and both the magical and the hopeless contours of the plot leave you with little idea what’s going to happen next except the feelings of wonder and dread uncoiling in your stomach.

This is a rich example of what language can do, and its handling of scent is masterful and luscious. Like a skilled nose, Erica Bauermeister embraces light-handed subtlety in blending together all the notes of this book. I begrudge singing this book’s praises because it hurt so much almost the whole way through, but it is an excellent example of craft, and one with elements that are ultimately rewarding after persevering through wave after wave of casual day-to-day heartbreak.

This story is going to stick with me for a long time for its beauty, tenderness, and hope. If you think you can handle the grief running deep through The Scent Keeper, I recommend it wholeheartedly.

One thought on “The Scent Keeper by Erica Bauermeister Book Review”